Seeing only what we know

A look at our role in perception and its implications for social life

In 1910, a pair of French doctors documented their surgery that gave sight to an 8-year-old boy who had been blind since birth due to cataracts. Once the boy had healed, the surgeons removed his bandages, anticipating a miraculous moment of newfound sight.

Yet, when they waved their hands before the child's newly functional eyes and asked what he saw, the boy could only muster a bewildered "I don't know." Even when pressed about their hands’ movement, his answer remained unchanged. Though his eyesight was functioning, the boy could only recognize changes in light. He couldn’t perceive shapes or motion—even the moving hand in front of him.

Only when allowed to touch the moving hand, the boy exclaimed with certainty, "It's moving!" What was once unintelligible to the child—the sighted movement of hands—disclosed itself through his capacity to intuit new relationships in his immediate experience. Bringing his conception of (unsighted) “movement” to the raw sensations of his senses—touch, hearing (he said he could “hear it move”), and now vision—the boy transformed his undifferentiated experience into meaningful perception.1

We often think of perception as mere passive reception. Our eyes see something, then we understand. But as this case suggests, an optically healthy eye on its own is insufficient for sight. Perception calls for activity on our part. The boy had to think the new relations to perceive them. Without this thinking activity, the moving hands would have remained an indistinguishable riddle in his visual field. Only grasping the idea of “movement” allowed him to see it. (This phenomenon is often associated with the Molyneux's problem and I’ve listed more research accounts of it below.2)

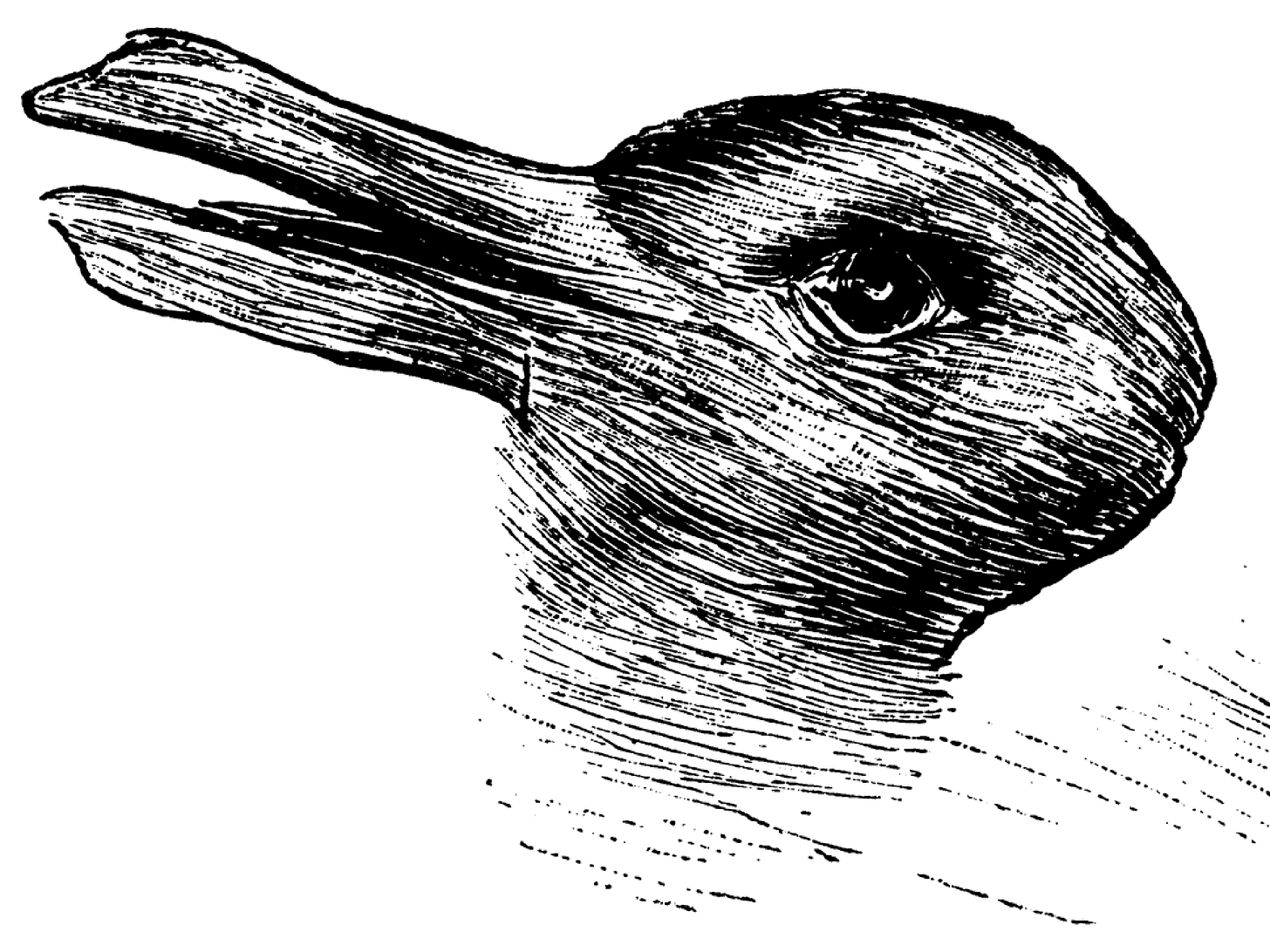

For those with functioning vision, let's examine three visual experiments to experience how we participate in our perception. Spend a few minutes looking at Figure 1. You might first recognize either a duck or a rabbit, but never both at the same time. If you need help seeing them, try glancing to the left to see the beak of a duck, and glancing to the right to see the mouth of a rabbit.

Once you’ve seen both the duck and the rabbit, fix your eyes on its eye, widen your attention to the whole image, and practice shifting between the two representations. Pay attention to your inner experience just before the duck becomes the rabbit and the rabbit becomes the duck. What is happening? One of the immediate insights is the active nature of our perception. To see the duck, we mentally intend “duck-ness”—to see the rabbit, we intend “rabbit-ness.” To recognize a certain figure, we must look at the image in a certain way. We bring specific relations to it. Shifting back and forth increases our awareness of the (usually) unconscious process that prepares our everyday perception.

Let’s try something more abstract. Take a look at this image created by Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa (Figure 2). You might immediately recognize a white square atop four black circles. However, looking closely, no lines delineate a white square; our mind unconsciously prepares that representation for our perception. Now, try to see only “four black, three-quarter circles.” It’s a bit harder, but the whole image changes. Practice shifting again to consciously experience our active role in perception.

Let’s look at a final example, more challenging than the previous two. Consider Figure 3, designed by psychologist Akiyoshi Kitaoka. You may initially see red appearing in front of blue, or the reverse, blue appearing in front of red. Others might see red and blue appearing flush. Now, try intentionally switching between each of these representations. This may be difficult, but I promise it’s possible. By intending different relations, we perceive different images.

The experience of shifting representations clarifies how we participate in perception. The relations that arise in our perception (e.g., a duck, a white square, blue behind red) are evidence of the relations we intend to see (e.g., “duck-ness,” “white-square-ness”, “blue-behind-red-ness”) even when we’re unconscious of that activity. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe spoke to this idea when he said, “We see only what we know.”3 What we “know,” from Goethe’s perspective, are the relations we propose to a phenomenon under observation, mirrored back to us in perception. In everyday experience, this happens instantaneously, seemingly independent of our participation; we see the relations we first (unconsciously) intend. When we intentionally see an image in multiple ways, we bring to our awareness the usually unconscious activity whereby a phenomenon becomes intelligible.

Without the right intention, or any intention at all, we cannot grasp the relations that reveal something to our perception. Consider the experience of a "double-take." We encounter something we don’t understand at first glance and need to look again. Once we recognize the correct appearance, we understand that the thing was always itself and we just initially misperceived it. We thus become aware of our causal role in the initial failed glance but rarely the correct second. When we propose ideas that don't align with reality or its possibilities, we further illuminate the ways in which our experience is mediated by how we perceive.

Experiencing our causal role in perception can help us reappraise our everyday thoughts and observations. The world gradually transforms itself from a mere presentation given to our senses to a living conversation. What we “say” to the world is “spoken” back; like a conversation with a good friend, the world and ourselves start and finish each other’s sentences. The knowledge we derive from these conversations is a correlation between what is seen and how it is seen. Indeed, as we experienced above, the distinction between the two collapses; they are identical in nature yet represent different “ends” of experience (subject and object). All of (our) experience then depends on how we choose to speak to the world.

The possibility to contribute original dialogue with the world hinges on our capacity to intuitively perceive newness in experience. Einstein described intuitive perception in this way: “There comes a point where the mind takes a leap—call it intuition or what you will—and comes out upon a higher plane of knowledge, but can never prove how it got there. All great discoveries have involved such a leap."4 The “leap” our minds take to perceive something new—like the boy recognizing "sighted movement" or the seeing of “red behind blue” for the first time—reveals how we comprehend newness from experience rather than create it from nothing. Just as “movement” and the “duck” existed as ideas before they were recognized, so too did humanity’s great achievements. As J.R.R. Tolkien said of the epic tales within his Lord of the Rings universe: “They arose in my mind as “given” things, and as they came, separately, so too the links grew…yet always I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere: not of inventing.”5 Intuition empowers humanity to perceive what is inherent yet unrevealed in experience.

The intensity of our intuition corresponds with our attentiveness to originality in experience. When we shifted between image representations, we noticed the process of intending the ideas that we come to see. Intuition works similarly, but instead of proposing preconceived notions, we offer a gesture of genuine receptivity: beholding. In doing so, the phenomenon reveals itself to our thinking, like presenting a gift. Place an ordinary pebble in front of you, and make note of its shape, features, and lighting for several 30-second intervals. Notice the new, seemingly endless details flowing forth in your mind. Devoting our attention to the revelation of another gives rise to the new, the fundamental quality of existence. This intuitive capacity can be strengthened with practice, and as it develops we can distinguish the immense difference between intuitive knowledge (derived from phenomena) and intellectual facts (abstract constructions). We can even experience the birth of new ideas. As Simone Weil noted, "Extreme attention is what constitutes the creative faculty in man and the only extreme attention is religious."6

None of this is to suggest we abandon our critical thinking, deny the world’s injustices, or discount the (daily) errors of our thinking. Nor is it to suggest our brains play no role in perception. Rather, this is an invitation to contemplate the totality of our immediate experience, setting aside our favorite scientific theories and personal stories just for a moment. By doing so, we can encounter for ourselves the possible intensification of thinking, moving through the intellect to greater levels of sensitivity, curiosity, and understanding. These capacities aid our everyday thinking, awareness, and problem-solving. I may never overcome my habits of jumping to conclusions or judging another’s character, but I can become more aware of their destructive quality. The north star is active receptivity to phenomena as they are.

There’s plenty we can all say about perception and social life. For now, I will only share the importance of preserving in our perception both humanity’s highest potential and our infinite source of creativity—the nature of our being. Doing so helps us recognize this highest potential in ourselves, other individuals, and whole groups of people—and avoid foisting our narratives onto others. Sensing the abundance of our creativity helps us also recognize the abundance in Earth’s resources (assuming we learn to live within its boundaries). Many influences seek to diminish, deny, or obscure our potentials as well as the abundance in our creativity and nature. The temptation to host these influences constrains our experience, and in doing so hinders our ability to perceive the capacities our social challenges invite us to develop. We meaningfully engage our challenges when we (finally) experience them in the context of our capacity to grow. Indeed, this is where the healing nature of perception lies. Only love in its deepest sense—the sacred hosting of another’s being—brings us to the experience of knowing who we are in light of who we are becoming. Like the boy who perceived movement for the first time, humanity itself is the potential to recognize new capacities lying dormant in experience.

This story was found here: Arthur Zajonc, Catching the Light: The Entwined History of Light and Mind, Oxford Paperbacks (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1995). And adapted here.

Additional perspectives on newly sighted perception, translated by Henrike Holdrege: Kiel M. von Senden, Die Raumauffassung von Blindgeborenen vor und nach ihrer Operation, (1931). Contemporary research may be found at the Prakash Project.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Gage Educational Publishing, “Introduction to the Propyläen”, Goethe on Art (London: Ashgate Publishing Group, 1980), p. 7.

William Miller, “Death of a Genius,” LIFE, May 2, 1955.

Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien: A Biography, (New York: George Allen & Urwin. 1977), p. 103.

Simone Weil and Gustave Thibon, Gravity and Grace, trans. Emma Crawford and Mario Von der Ruhr, 1st complete English language edition (London New York: Routledge, 2002), p. 117.

What a beautiful post and such a great explanation of Goethean observation. I love the quote about "extreme attention"!